Duluth to Montgomery: Lynching memorial 'overwhelming'

This story was originally published on May 8, 2018, but has been updated with additional content.

Elmer Jackson was one of the reasons Kim Green went on the trip to Alabama with a busload of strangers.

But it was another Jackson — the city — that stopped her in her tracks.

"That's where my people are from," Green noted standing inside the National Memorial for Peace and Justice during its grand opening April 28.

Create a More Connected Minnesota

MPR News is your trusted resource for the news you need. With your support, MPR News brings accessible, courageous journalism and authentic conversation to everyone - free of paywalls and barriers. Your gift makes a difference.

Green looked at a steel slab hanging from atop the structure that documented the 22 people known to have been lynched in Hinds County, Miss. The city of Jackson is located in Hinds County.

County names are etched on each of the 800 slabs that hang in the somber memorial serving as a visual reminder to America's not-so-distant past where racism ended in murder.

"It's too many, it's too many," Green said as she teared up while counting the names from the county where her grandparents lived.

"It's overwhelming."

Among first visitors

Green, 53, was one of nearly three dozen Minnesotans who took a 98-hour bus trip from the hills of Duluth to warm streets of Montgomery, Ala., to be among the first to tour the memorial and attend the museum's opening.

"It's too many, it's too many ... It's overwhelming."

The group made stops along the way: In Cairo, Ill., they saw the site of a lynching in 1909, in Memphis, Tenn. They visited the National Civil Rights Museum built into the Lorraine Motel where Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in 1968. In Birmingham, Ala., they visited Kelly Ingram Park, considered the staging ground for several important demonstrations during the civil rights movement.

They came to learn ways to keep the spotlight on a harsh past most don't learn from textbooks. They left Duluth determined to see how Minnesota would be represented at this new 6-acre memorial and museum site, and how the story of lynching can be better told back in Minnesota.

Some also came with their own family trees in tow, seeking a connection to a part of American history far away from Duluth.

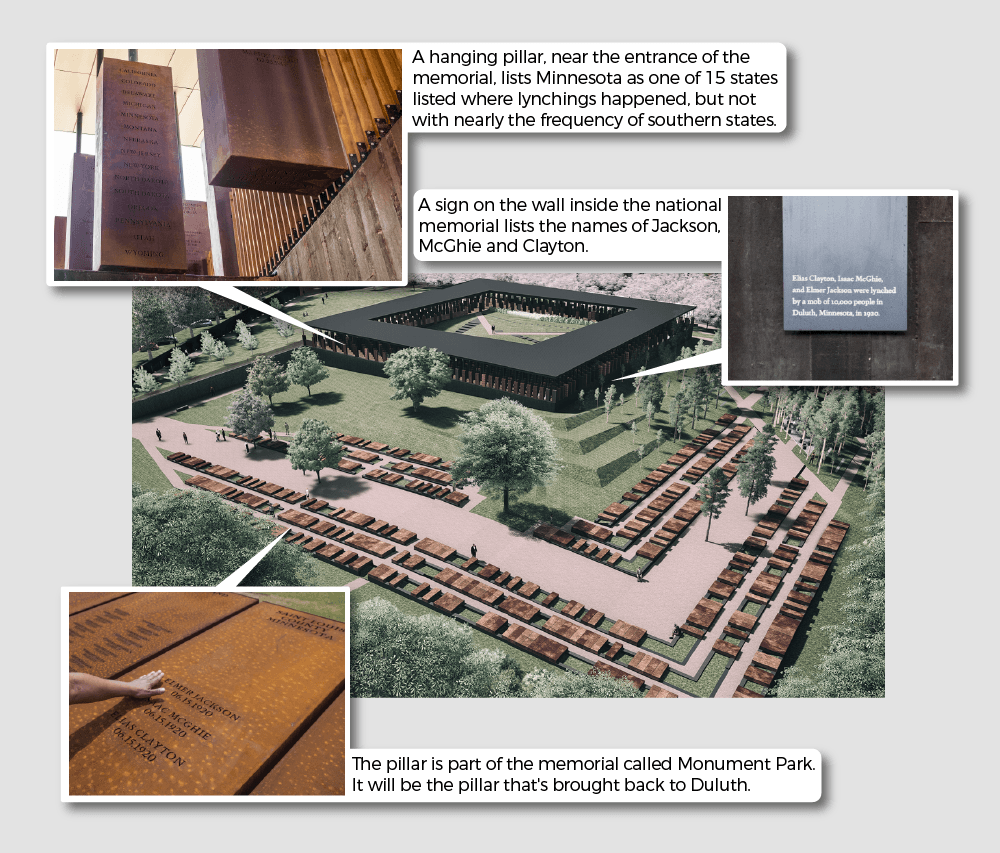

Duluth is the site of the only documented case of the lynching of black people in Minnesota. On June 15, 1920, Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie were lynched by a mob of thousands in Duluth who believed the three African-American circus workers had raped a 19-year old woman. The woman's claims were never found credible, including by a doctor who examined her after the alleged assault.

Duluth is also believed to be home to the first-ever memorial to a case of lynching. Green sits on the board that oversees that memorial. The trip was designed to travel from a memorial that remembers one lynching to a new memorial that remembers all of them.

More than 4,400 African-American men, women and children were killed from 1877 through 1950 in the United States, according to the Equal Justice Institute.

The Institute, which operates the new memorial and museum, now broadens not just the number of men and women who were killed but hopes to expand the narrative that slavery hasn't ended in the United States, but has evolved. It aims to make the point that instead of dying on ropes in the public square, black men are now dying in American prisons.

Host Tom Weber looked back at his bus ride from Duluth, Minn. where three black men were lynched in 1920 to Montgomery, Ala. for the opening of a memorial to honor the thousands of African-American men, women and children that were lynched in America. Green's family moved to Duluth decades ago to work in the city's steel mills; gainful employment was the reason most people learn for the Great Migration of blacks from the South to the North in the first half of the 20th century. But lynchings are also an important reason why blacks left the south — they were oppressed, silenced and scared into leaving, according to EJI. "Thousands of people fled to the North and West out of fear of being lynched," according to an EJI report said. "Parents and spouses sent away loved ones who suddenly found themselves at risk of being lynched for a minor social transgression; they characterized these frantic, desperate escapes as surviving near-lynchings." The message is clear: Even for a state like Minnesota, which has only one documented lynching of black men in its history, plenty of Minnesotans have deep roots in states where the mob attacks were regular occurrences.

'It's a war that's still going on for us'

Kym Young, of Superior, Wis., was another member of the Duluth-to-Montgomery bus trip contingent. She teared up upon seeing the gathering of more than 800 slabs representing each county in the U.S. where a lynching is known to have happened — hanging in a way to mirror the way lynching victims were hanged.

"This was the price we pay for freedom we're still fighting for. It's a war that's still going on for us," Young said. "And it makes me wonder, how big will this memorial get?"

Young, 52, grew up in Roanoke County, Va., before moving to Minnesota in her 20s. "When I grew up, I was taught that we lived in the gentile South; that it wasn't as bad as the Deep South, where most of the lynchings took place.

"But I'm pretty sure it's here; I'm sure it's going to tear me up as much as what we have for Duluth," she said.

A few minutes later, after walking along an interior plaza inside the memorial, Young found the marker for Roanoke County, with two names inscribed: Thomas Smith and William Lavender. The men were lynched in separate attacks in the 1890s.

"We were never told about lynchings there but I knew we had to have some," added Young. "Even just two is two too many."

Young now lives in Superior and founded an organization called Superior African Heritage Community which, among other things, organizes the city's yearly Juneteenth event.

Since the trip, she says she's contemplating writing a book about it. As she gazed upon the monument, she remarked on the solace she found in the pain of finding her home county documented:

"It's helpful to know our country is finally coming to recognize and trying to make amends," she said.

"But we have a very long way to go," she added. "And this is the first step."

Minnesota's legacy at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice

There are three places where Minnesota is represented at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala. Elmer Jackson, Isaac McGhie and Elias Clayton were hanged from a light pole in Duluth by a mob after a woman claimed she was raped in 1920. Her claim was never found to be credible.